How to move the elephant: A lesson for design consultants

Large organizations are complex, powerful and difficult to move. Drawing on the metaphor of the elephant, this article explores why traditional consulting approaches often fall short—and why meaningful change requires the integration of systems thinking and creativity, working together to shape solutions that truly move organizations forward.

In the middle of a room stands a large elephant. With eyes closed, a group of people forms a circle around it. Each person begins patting and poking the beast from their unique angle—trying to figure out what this massive object might be. “It’s the rope of a ship!” “It’s a tree trunk!” “It’s a spear of ivory!” they shout. They argue fiercely, each unable to see the full view.

I’ve always been fascinated by the elephants of the world—giant organizations, companies, nonprofits, governments. What makes them up? How do we see them? Why do they fail? To be successful, these elephants often seek advice from the outside—from consultants. Your elephant’s tusks aren’t looking so great? There’s someone to help redesign them. Need stronger legs? That can be arranged. Can’t figure out what direction your elephant should be walking? There are plenty of people to help steer you in the right direction.

As a designer, the kind of advice I give these elephants has always been “creative.” I remember starting as a freelancer and thinking I held the key—that my creative approach would yield the most genius idea for how to help this one organization. My designs were gold, hand-crafted and kissed by the divine. But after being implemented, I’d realize I’d only draped a red kimono over the elephant, prettying it up but not fundamentally changing it. My solution was gold-foiled, maybe, but nowhere near 24-carat.

After working alongside different types of consultants (not just creatives), I realized this problem is common. Consultants commonly end up in one of two camps: 1) You’re grounded in hard-core strategy or operations, in the decisions of the C-suite, but you struggle to genuinely understand the people—customers, constituents, communities—they serve, or 2) you’re on the product or advertising side and create brilliant work, but it doesn’t end up aligning with where an organization really should be headed. The key is understanding and leveraging both strategic and creative approaches.

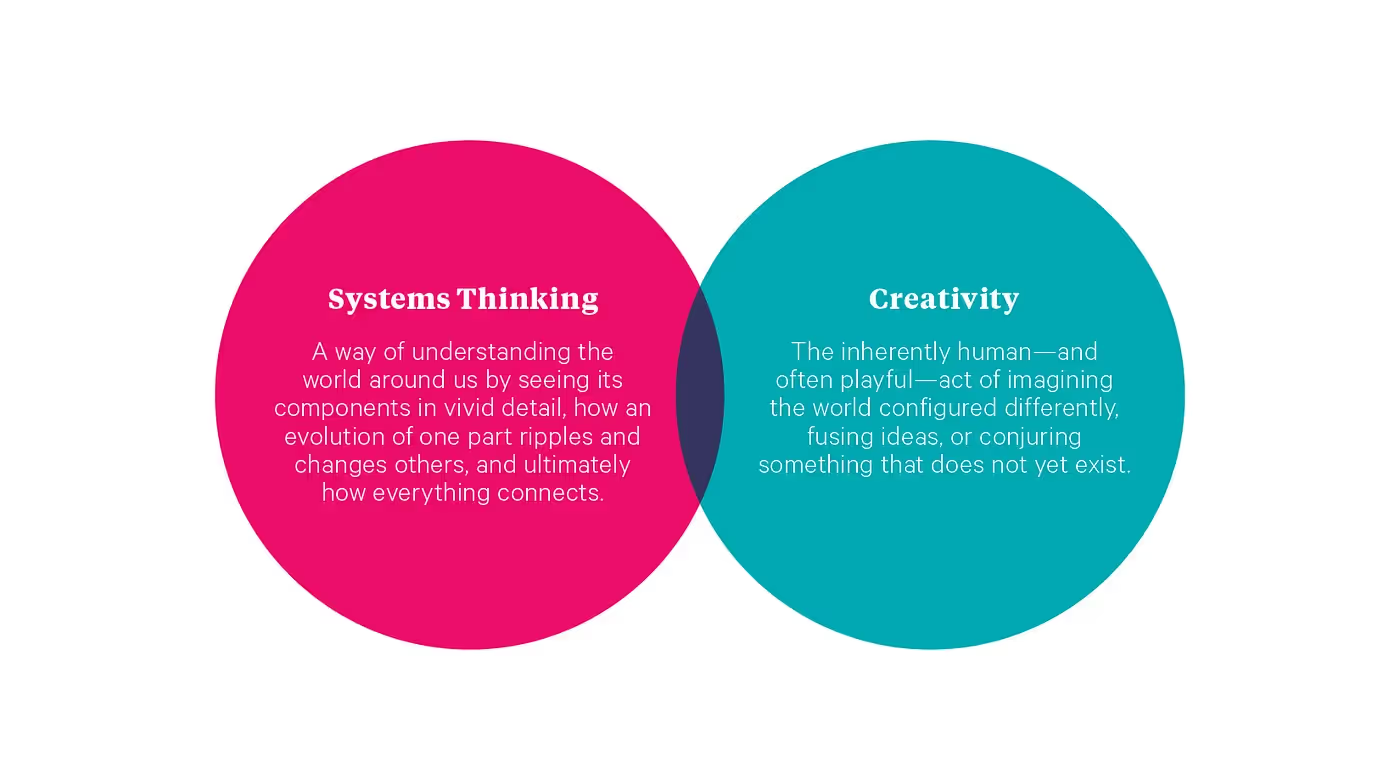

When functioning at their highest level, design and strategy really are two sides of the same coin. Rather than one specialty being in service of the other, they must run in tandem. This seems simple, but is surprisingly difficult in practice. Forget a back-and-forth handoff between practitioners—between “thinkers” and “makers,” between logic and imagination. Consultants who have the most impact exercise both systems thinking and creativity.

What do I mean by this? When I first started working at SYPartners, I caught a glimpse of how systems thinking and creativity blend together, in practice, to make great work. In 2014, a team of SYPartners strategists and designers were tasked with creating a physical piece that would move the hearts and minds of its audience around the subject of race in America. The output became A Compendium on Race.

The piece—a collection of images, articles, facts and ideas on the topic—was beautiful to be sure. But here’s why it resonated with me: Every element was evidence of a fusion of systems thinking and creativity.

To present a provocative and meaningful piece on race relations, you first need to understand the thorny history of segregation in this country. You need to take into account how this history remains prevalent in society today, and how it differs for various age groups. You must observe how race is discussed in popular culture—and even in unpopular culture, if there is such a thing. You need a wide-ranging, yet thorough, understanding of the issue—a systems-level view. And with all the recent events happening in this country, this is more important than ever.

Armed with this systemic view comes the tricky design challenge: create an entry point into a topic riddled with fear of saying the wrong thing, perceived stereotypes and basic misunderstandings. The team came up with creative ways to address this—by juxtaposing familiar messages in unexpected ways, and focusing on simple ideas coupled with vivid imagery. Content complemented design, and vice versa. They were inseparable—two sides of the same coin.

Soon, I combined systems thinking and creativity myself on a consulting project at SYPartners. One late night, my team debated a bite-sized deliverable for a client: How should a set of interview cards read, and what visual form should they take? Working side by side, our strategists wrote a series of thoughtful questions for the cards, and our design team laid them out—three-color Pantone, double-sided, 80-lb paper with rounded corners. But we ran into a conundrum. We’d be printing thousands of these kits, as our project manager reminded us, and three-color Pantone with rounded corners would be a multi-thousand-dollar cost addition.

So our team began to ask bigger questions: Who would be asking the questions on these cards, and how would they engage their audience? What value would they place on the cards, and how frequently would they be used? And what should we make to meet these realities? Half-size cards with shorter questions and still rounded corners? Larger single-sided cards in multicolor with questions plus instructional statements? Were these decisions justified?

Of course, this was designing at the level of elephant toenails. But this degree of thoughtfulness—constantly zooming in and out to see the full scope of our creative and strategic decisions—scaled up to the most important decisions of the project. Our solution didn’t compromise on content, still felt physically valuable and made sense for the community we intended to serve. And since you’re probably curious—we ended up with one-color, double-sided 80-lb paper without rounded corners.

The point is, designers should aim to stretch their abilities beyond traditionally defined creative work—to be deeply involved in the content and driving strategic questions. This balance is one of the most difficult things to create in the workplace, but it’s the thing I’ve come to appreciate the most. And it goes both ways: Strategists should be embedded equally in the design process.

I often think about a talk John Cleese gave in the early ’90s for Video Arts. He argues that creativity is not an inborn talent, but rather a “mode of operating.” I think it’s even bigger than that. Being a creative company is not just about hiring more designers or strategists—it’s also about getting everyone to show up in this creative mode of operating. It’s what lands brilliant ideas and sets the elephant in the right direction.

More MOMENTUM

Leading without a playbook starts with Vision

In moments of uncertainty, speed without direction creates fragmentation. A clear vision aligns decisions, investments and imagination around a shared future. When old strategies no longer apply, vision becomes the anchor that helps leaders create the path forward rather than chase it.

Developing a strategy is a rehearsal of the future

Strategic planning now demands the discipline to imagine multiple futures before choosing a path. In volatile markets, fixed plans fall short; grounding strategy in Purpose and Vision keeps decisions, investments and priorities aligned, even as conditions change.

How to manage complex stakeholder interests? Think like a designer

As stakeholder capitalism reshapes how companies create value, leaders face a growing challenge: balancing complex, often competing demands. Managing stakeholder interests requires more than statements or promises. A design-led approach offers a practical way to make better decisions, align strategy, and build trust across stakeholders.