The negative space of culture

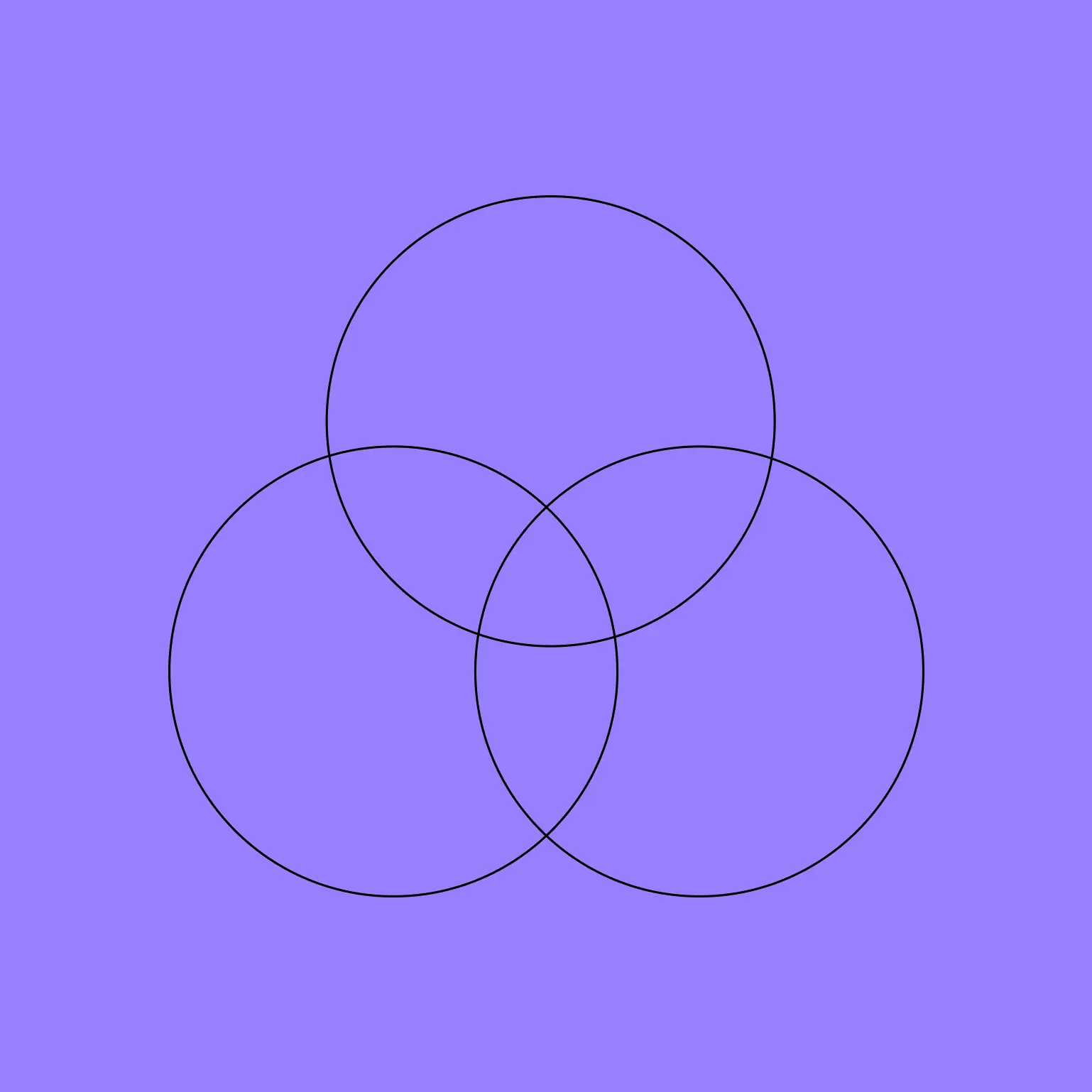

Culture is not defined by values statements alone, but by the boundaries leaders enforce under pressure. Drawing on the idea of negative space, this article explores how culture is shaped by what leaders tolerate, interrupt, and protect—and why clarity at the edges matters more than aspiration at the center.

To bring culture into focus, leaders must look to its edges and ensure alignment between what is said, what is done, and what is tolerated. Culture is not proven by aspiration alone. It is proven by what leadership allows and what it is willing to interrupt, especially under pressure. There’s a principle in drawing: You don’t focus on the object itself, but on the space around it. The shadows, the edges, the negative space. That’s what gives the subject its definition. After over a decade of working with senior teams to shape culture, I’ve seen the same pattern repeat. Leaders invest significant energy articulating values and setting direction, yet far less attention is paid to the boundaries that actually govern behavior. Culture shows up in what leaders reward and protect, and in what they excuse. In the decisions they make visible, and the ones they quietly step around. When boundaries are unclear, culture becomes diffuse, regardless of how clearly it is articulated.

A practical frame for culture

When culture is working, three elements are consistently aligned:

- What we say: The values, principles and commitments leaders articulate.

- What we do: The behaviors leaders model, reward and promote, particularly under scrutiny.

- What we tolerate: The behaviors leadership chooses not to address, often in the interest of speed, harmony or performance.

Most organizations focus heavily on the first two. The third is where culture is ultimately decided.

When alignment is strong

Patagonia is often cited as an example of cultural alignment, and for good reason. The company states a clear purpose: to protect the planet. It backs that purpose through sustained investment in sustainable materials, public advocacy and legal action when necessary. Just as importantly, it draws firm boundaries around behaviors that contradict that mission, even when doing so introduces cost or friction. In 2017, it sued the U.S. government over public-lands protections and withdrew from major industry events in protest of state policy, signaling that environmental commitments would outweigh convenience or commercial comfort. The edges are explicit. That clarity reinforces the culture at scale.

When alignment breaks down

Now consider a more common scenario: An organization publicly commits to equity and inclusion. It publishes codes of conduct and formal policies. Yet discriminatory or harmful behavior is tolerated when it comes from high performers, senior leaders or individuals deemed too difficult to confront. In those moments, leadership is still defining culture—just not in the way it intends. Under pressure, when stakes are high, timelines are tight or power dynamics are uneven, what leaders tolerate becomes the most credible signal of who the organization is and what it truly values.

Putting it into practice

For leaders, this work is less about new language and more about clearer decisions:

- Identify the subject. Be precise about what matters most. Strip away generic language and identify the few principles that truly guide decision-making.

- Find the edges. Make explicit tradeoffs. This over that. Name dealbreakers and the behaviors that cross the line, regardless of role or performance.

- Bring it into focus. Identify where misalignment exists between stated values, daily decisions and tolerated behavior. These gaps are not abstract. They are already shaping performance, trust and risk.

When culture feels unclear, the issue is rarely a lack of vision or communication. More often, it is a reluctance to challenge what has become normalized. Culture does not blur because leaders do not know what they stand for. It blurs at the boundaries they hesitate to enforce. Look at the edges. That is where culture is drawn.

More MOMENTUM

What Agile taught me, and why nimbleness matters more in an AI era

Agile reshaped how organizations learned to move faster in a digital world, but its lessons are being tested by AI. As leaders race to pilot and scale new capabilities, speed alone is no longer enough. This article explores why nimbleness—more than any single methodology—may define responsible AI adoption and long-term relevance.

Winning in disruptive times starts with Culture

Organizational culture is a strategic asset, not a collection of perks or posters on a wall. It grows from shared purpose, is embedded in the operating model, and shows up in how people work and collaborate every day. When culture is intentionally designed and reinforced, it becomes a durable source of performance and resilience.